Optimism After West Virginia v. EPA SCOTUS Decision

On June 30th, 2022, a 6-3 majority of the Supreme Court officially laid the 2015 Clean Power Plan (CPP) to rest. Initial reports have pitched the outcome as a disaster, and the dissenting opinion makes it seem that way too, at times. But as the dissent also notes, the CPP had been dead in the water for years. Biden’s EPA didn’t want to resurrect it, and the plan’s proposed emissions targets have already been surpassed (see Figure 1 below). Other regulatory tools would have been—and still can be—impactful; the majority left intact EPA’s obligation to regulate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from existing power plants. EPA has multiple paths forward—which is a serious silver lining for climate policy.

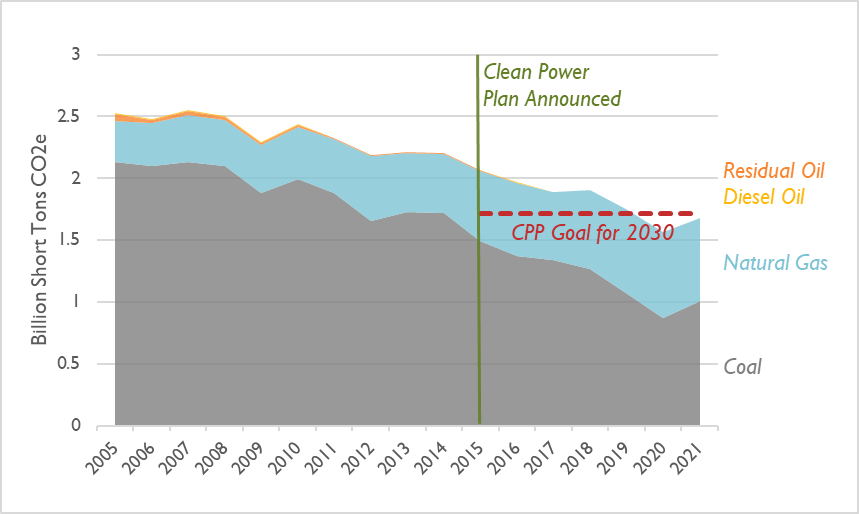

Figure 1. U.S. Power Sector Emissions by Fuel Source

Coal-fired generation was already in decline prior to the announcement of the Clean Power Plan. Although the plan never went into effect, continued economic trends allowed power sector emissions to reach the Clean Power Plan’s 2030 emissions goal in 2019.

This was not the outcome many expected. The case, West Virginia v. EPA, was widely seen as a chance for the conservative majority to strip EPA of its authority to regulate carbon dioxide (CO2) entirely. Instead, the majority focused narrowly on whether EPA can impose an emissions cap based on the concept of “generation shifting” through its authority under the Clean Air Act.

Generation shifting was the backbone of the Clean Power Plan’s goal to reduce CO2 emissions from the power generation sector. President Obama’s EPA invented the term when it determined that the “best system of emission reduction” for CO2 was to shift electricity generation industry-wide, initially from coal-fired generation to natural gas-fired generation and eventually from all fossil fuels to renewables. To compel that shift, the CPP offered states the option of participating in a national cap-and-trade system.

According to the majority opinion in West Virginia v. EPA, this regulatory approach differs from the way EPA typically regulates pollutants. It points out that in the 50 years since EPA’s conception, the agency has often used cap-and-trade systems to manage emissions, but they’ve always been predicated on a facility-level performance standard, not industry-wide goals. Those standards are set one of two ways: (1) at a level determined by an objective, science-based impact study, or (2) at the level achievable through the best available pollution-control technology.

According to SCOTUS, imposing a cap-and-trade system to deliver a generation shift at the grid level requires a wider reading of EPA’s authority. The question at the heart of West Virginia v. EPA was whether Congress intended for EPA to have that power. The answer may officially be no, but EPA retains its ability to set performance standards for individual power plants, giving the agency multiple options for limiting CO2 emissions nationwide.

EPA’s Authority Under the Clean Air Act

EPA’s authority to regulate power plant emissions stems from two sections of the Clean Air Act: 111(b) and 111(d). Section 111(b) charges EPA with the responsibility to regulate pollutants from new or modified stationary sources of emissions. Section 111(d) does the same for existing sources.

In 2015, EPA set a CO2 performance standard under 111(b) for all new, fossil-fuel-fired, steam-generating power plants (which includes essentially all coal-fired generating units) equivalent to the performance of a new, supercritical pulverized coal boiler implementing partial carbon capture. The technology-based standard is so strict that new coal plants effectively cannot compete with cheaper gas and renewables, which is a large reason why almost none have been built since. The 2015 rule still stands, untouched by West Virginia v. EPA. EPA retains its ability to limit new power plants’ CO2 emissions.

Section 111(d), which pertains to the regulation of existing fossil plants, is the statute at issue in West Virginia v. EPA. The majority opinion is clear:

“Congress did not grant EPA in Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act the authority to devise emissions caps based on the generation shifting approach the Agency took in the Clean Power Plan. […] EPA claimed to discover an unheralded power representing a transformative expansion of its regulatory authority in the vague language of a long-extant, but rarely used, statute designed as a gap filler.”

That sounds dramatic. So does the dissenters’ opening paragraph, which states that the decision “strips the Environmental Protection Agency of the power Congress gave it to respond to the most pressing environmental challenge of our time.’” On the other hand, the majority and dissenting opinions both emphasize that EPA is still responsible for setting performance standards for CO2 and suggest that it can in the two ways it always has—through the best available technology or objective science.

As the dissenters point out, if EPA had based the CPP on either of those methods, the policy might still stand: “EPA could have designed the Clean Power Plan […] by setting emissions limits based on carbon-capture technology, with the expectation that many plants would avail themselves of an approved cap-and-trade program instead.” Further, the dissenters acknowledge that “The Clean Power Plan, we now know, would have had little or no impact,” and that “a rule requiring the use of carbon-capture technology would have shifted far more electricity production from coal-fired plants than the Clean Power Plan would have.” Following West Virginia v. EPA, that exact route may still be an option for EPA.

The big question now is what EPA’s next 111(b) rule will look like. EPA is hardly toothless, but the full implications of West Virginia v. EPA are still debated. Given time to analyze the decision, however, EPA’s next rule should be on even firmer ground. There is plenty of room for hope and optimism.